Stress stimulates appetite, it increases abdominal fat, it increases risks for disease and it can even play a role in our intimate relationships.

The list could keep going, but what exactly is stress and how is it connected to all these consequences? This guide will provide you with a thorough understanding of many aspects of stress.

- A definition of stress

- The harms and benefits of stress

- How mental perceptions affect stressors

- Stress in males vs females

- Metabolism

- Cortisol – its benefits and detriments

- Stress management techniques

Scroll down to get started!

What is Stress?

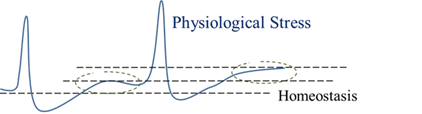

Stress can be is defined as a nonspecific response to any stimulus that overcomes, or threatens to overcome, the body’s ability to maintain homeostasis (state of equilibrium of the body’s internal biological mechanisms) (1). In other words, when the body is exposed to, or anticipates a stressor, it initiates a response mechanism to help restore a state of equilibrium.

However, it is important to remember that this biological response is essentially the same regardless of the type of stress we impose upon ourselves, and only differs by magnitude of the response needed.

A breakdown of the stress-response mechanism

Our stress-response mechanism is designed to respond to acute physiological stresses – ones that place stress upon our body for only short periods of time (e.g., escaping a sabre-tooth tiger) where we respond with physical work.

We often refer to this mechanism as our ‘fight-or-flight’ response. We either confront the stressor or remove ourselves from it (1). The stress is short-lived and allows ample time for the body to recover from the stress response.

After we remove the stressor, the body theoretically seeks to return to a state of calm to re-establish baseline or homeostasis, or perhaps undergo adaptation to tolerate future exposure to that same stressor better. This recovery phase ensures adequate time for each system (e.g., immune system) to complete any needed recovery, replenishment, repair, or adaptation and is illustrated below.

Mental perception and stress

Is stress harmful to the body? Is it something that should be avoided, managed, and reduced – or should it be embraced and utilized to benefit the body?

While no definitive answer exists, there is emerging evidence to suggest that while the manifestation of stress is mainly physiological, it may be the mental perception or interpretation of stress that ultimately dictates whether it is beneficial or harmful.

In a study conducted by Keller and colleagues, 30,000 individuals were tracked to determine their perceptions of stress and its impact upon mortality (Keller, et al., 2012).

As expected, individuals reporting low levels of stress experienced the lowest levels of mortality. In contrast, those experiencing high levels of stress demonstrated the highest risk of mortality, but the interesting discovery lay with the perception of how stress affected the body.

Those who did identify high levels of stress, but also believed that stress was not harmful to the body demonstrated similar mortality rates to those experiencing low levels of stress. Although this study faced some scrutiny, it paved the way for other studies that examined the same notion of mental perception as a key indicator of the effects of stress.

The two Stress-Response Mechanisms

To better understand this difference, it may be helpful to first review key stress-response mechanisms. Our biological stress response was designed for survival and is regulated by both the neural and endocrine (hormonal) systems.

The nervous system is a rapid-acting, but short-livedcommunication system that functions by transmitting nerve impulses – it reacts very quickly to stimuli, but its effects do not last very long (e.g., the sudden, short-lasting elevation of heart rate when startled).

The endocrine system is a slower-acting, but longer-lasting communication system that functions by hormonal action – it is activated more slowly (sometimes by nerve activity) and its effects may last longer (e.g., the sustained elevation of heart rate during a 60-minute run).

STress Reponses and their physiological influence

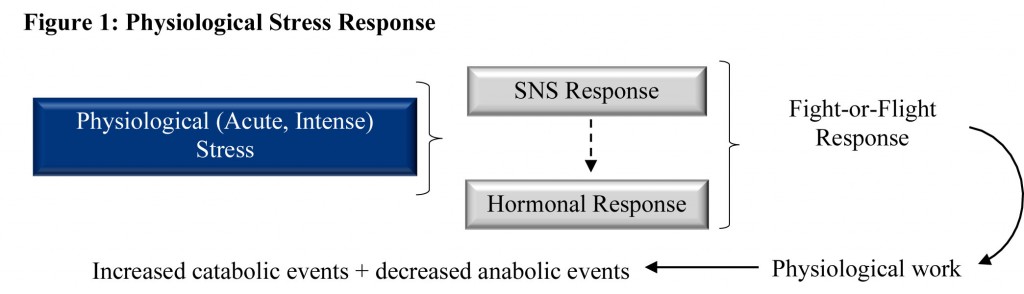

Our ancestors’ primary stressors involved a fight for survival or to the death against a predator or aggressor and the nature of the stress was an intense, acute physiological response (Figure 1).

However, after this brief, but stressful encounter, what followed was ample recovery to return to baseline (state of calm – parasympathetic or PNS dominance).

This allowed each physiological system (e.g., immune system) time to restore and regenerate itself after fighting to maintain homeostasis.

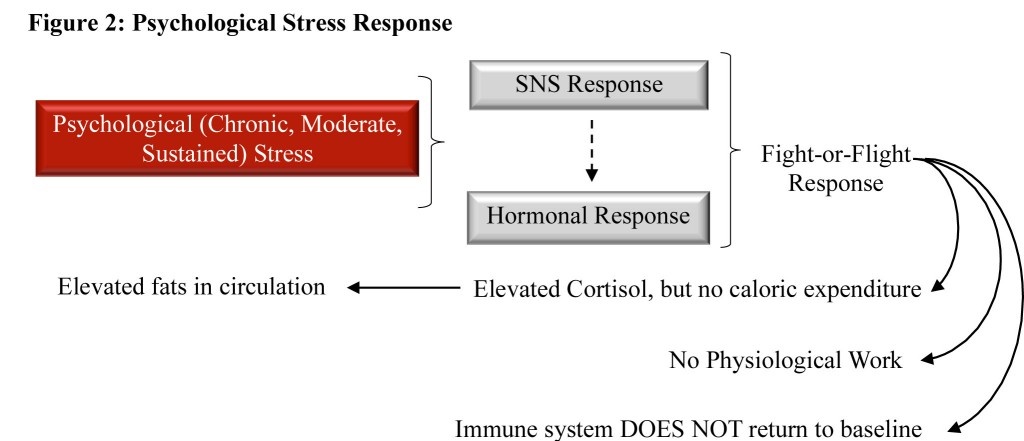

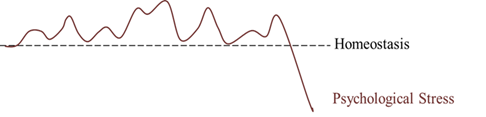

By contrast, today’s stress generally involves lower-intensity, sustained psychological stressors that sometimes never go away (chronic stress, or in extreme cases, PTSD) but accumulate (Figure 2).

For example, you might sleep through your alarm and wake up in a panic late for your meeting, skip breakfast, get delayed by a slow commute, arrive late for a presentation, get reprimanded by your boss, then finally make it to your office whereupon you receive a call that your child is sick and needs to be picked up from school – sound familiar?

These sustained stressors, although smaller individually, accumulate and deny the body that needed time to repair, recover and replenish.

Nonetheless, in either situation (ancestors v. present-day) the body activates its stress response in similar ways, albeit it at different intensities. And while we are familiar with many responses (e.g., increased heart rate and blood pressure, mobilization of stored fats, increased sweat rates), we may be unaware of others that merit concern (Table 1).

For example, elevated levels of epinephrine enhance blood clotting ability by increasing platelet adhesiveness (5). By design, this might be needed to stop one from bleeding to death during a survival fight, but think about this sustained effect upon cardiovascular health.

Ever wonder why you get dry mouth when nervous, why a dog urinates when scared or why you need to run to the bathroom before a big race?

Consider our need for survival – during a stress response, specific systems require additional resources, essentially borrowing from other systems deemed unnecessary during the ‘fight-or-flight’ response (e.g., reproduction, growth, maintenance).

In other words, some systems automatically shut down to provide the needed resources and energy to the critical systems and locations to facilitate survival (e.g., muscles, skin for thermoregulation). An example of this is saliva and digestive enzyme release in the mouth, stomach, and upper GI to facilitate chewing, digestion, and absorption shut down.

In contrast, the lower GI and bladder’s smooth muscle contractility become activated to void unnecessary urine and fecal matter that may slow you down in the event you need to run to survive. We list many of these allocations or resources in the table below.

Table One: Stress Response Influence on Physiological Systems

| Events Activated | Events Inhibited |

| Increased cardiopulmonary responses Increased vessel dilation in the needed location Increased mobilization of fuels Increased blood clotting ability Increased large intestinal contractility Increased bladder contractility Increased immune function – short-term Increased sweat rates | Decreased salivary and digestive enzyme secretion, and digestion Decreased stomach/small intestinal contractility Reduced pain perception (analgesia) Reduced growth, repair, and maintenance Decreased reproduction capacity Immune function – sustained long-term |

While these events are undoubtedly tolerable for a brief period (e.g., workout), think about these events’ consequences during a sustained bout of stress.

For example, blood clots more rapidly during an acute episode of stress to prevent excessive bleeding, but think to the health risk of a stroke or embolism if this effect lasted indefinitely?

What is cortisol and what are its benefits?

Cortisol is an essential hormone released from the adrenal gland in response to stress and provides many benefits:

- Sparing liver glycogen to ensure blood glucose preservation necessary for important physiological events like oxygen transportation to the brain by our red blood cells can only fuel themselves using glucose.

- Promoting the breakdown of stored fat within our adipose tissue to be used as fuel by muscle cells.

- Promoting fat uptake into muscle cells during activity.

- Suppressing continued cytokine synthesis and release following the acute phase of inflammation – a normal and healthy process. In other words, cortisol helps protect the body from potential detrimental consequences of an overactive immune response by acting in immunosuppressant capacity.

These events are modulated by and during the presence of cortisol under acute bouts of stress. Now, consider how exposure to stress has changed in humans living today. We have shifted from experiencing infrequent, acute, and short bursts of stress followed by periods of recovery to a lifestyle of sustained episodes of stress that do not include periods of recovery, as illustrated below.

The effects of elevated cortisol levels

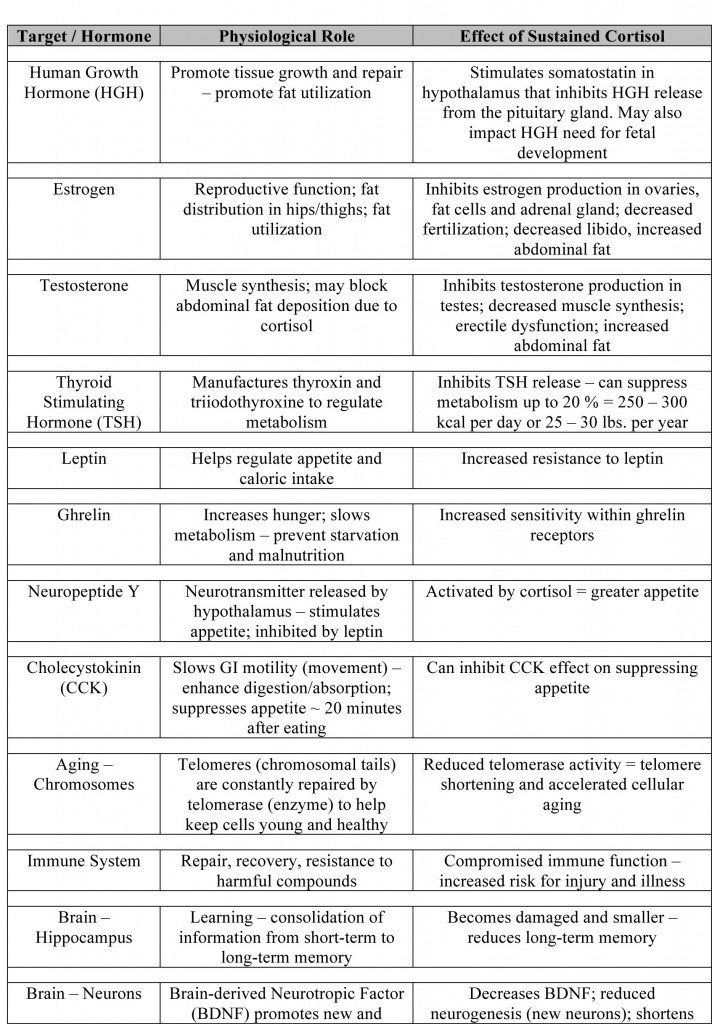

Consider the effects of sustained, elevated cortisol levels on the body’s physiological systems. Many of our planned interventions with clients and athletes focus on controlling appetite, increasing metabolism and fat utilization, building muscle mass, and reducing abdominal fat and overall body fat.

However, under sustained stress and elevated cortisol levels, the actions of many of the hormones responsible for these desirable events are impeded or even inhibited, including:

Stress + Cortisol can lead to an increased desire to eat

Furthermore, stress coupled with elevated cortisol can trigger an increased desire to eat given cortisol’s impact upon neuropeptide Y, a neurotransmitter in the brain that regulates appetites.

What follows eating is an elevation of insulin, which acts to inhibit fat metabolism within the body, another undesirable event.

STress Management Techniques

What stress-coping mechanism can you employ to help reduce your client’s stress levels? In addition to exercise as a stress management technique, there are many different techniques exist that demonstrate varying levels of success and while they should all be considered, select the one(s) most appropriate for your client(s) (7). Examples include:

- Deep Breathing (also known as paced breathing; belly, abdominal or diaphragmatic breathing):

- Find a place (physically or by clearing your mind) free of distractions.

- Close your eyes; and after a few normal breaths, draw in one long-slow breath through your nose engaging your diaphragm (include your chest – apical, if so desired).

- Pause momentarily, then slowly exhale through your mouth.

- Repeat for 30 – 60 seconds.

- Mindful Techniques:

- Start by repeating the breathing sequence, but now visualize relaxing scenes or visualize / repeat (slowly) any focus word or phrase that helps you relax.

- Practice in a place free of distractions 1 – 2 x per day for a minimum of 10 minutes each time.

- Variations of this technique include:

- Progressive mind relaxation – gradual intensification of the image, word or phrase.

- Mindful meditation.

- Yoga, Tai Chi or Qi Gong – including mind-body movements.

- Feldenkrais or guided imagery – super-slow (eyes closed) visualization inducing a deeper sense of mindfulness and mental imagery – often used to rehearse before movement.

- Body Sensation Awareness:

- Noticing subtle sensations (e.g., itching, tingling) without judgment – let them pass (progressive relaxation techniques).

- Progressive muscle relaxation – technique of visualizing tension release from muscles using sequential muscle contractions.

- Noticing emotions and feelings (e.g., anger, sadness) with judgment – accept them and progressively let them pass (diminish).

- Stored Energy Release:

- Stress can sometimes create muscle tension.

- For example, a gazelle under intense SNS activation that has eluded the interest of a predator proceeds to jump around after stress removal to release muscle tension. Similarly, humans also need physical sources for stress removal (e.g., exercise, punching).

- Reprioritization:

- Create opportunities to reprioritize matters – following a stressful event, spend time on an enjoyable activity or with person(s) who holds high priority in your life (e.g., hugging/playing with your kids).

- This helps prioritize and build perspective.

- Social Support:

- Studies examining primates and our ancestors demonstrated how females, following bouts of stress, resorted to affiliative behaviors such as grooming and hugging that offers a social calming effect (i.e., lowered blood pressure, cortisol levels).

- Research on oxytocin levels in female primates and human ancestors demonstrated more of a friend-and-befriend response rather than a fight-or-flight response, where they tend to their offspring and bond with one another when stressed (8, 9).

- For females especially, help plan and develop social support system that offers this same calming effect.

- Predictive Information:

- Awareness or anticipation of type, magnitude and duration of stress enables development of effective coping mechanisms.

- For example, planning ahead for a restaurant meal by reviewing the menu when trying to control caloric intake helps cope with the stress of making a rushed decision.

- Information however, must be relevant (i.e., tied to stressful event) and must be time-appropriate (e.g., information provided 3 weeks prior to, or one minute prior to ordering offers little help).

- Sense of Control:

- Creating impressions of or actually having control of a stressful situation can reduce stress.

- Low levels of control plus stress demands = poor stress response, whereas higher levels of control plus stress demands = better stress responses.

- With mild-to-moderate stress levels, increased control promotes self-efficacy.

- With high stress levels, one may benefit from less control to avoid extreme pressure, desperation or blame should they not succeed.

- Cognitive Flexibility:

- This involves developing the ability to remove stressors that you do control, but adapting to those stressors you cannot control. In essence, it helps one interpret things as always improving (i.e., positive outlook with glass half full).

- The Serenity Prayer by Reinhold Niebuhr, a 20th century Theologian helps summarize this strategy:

- “Grant me the serenity to accept the things I cannot change, the courage to change the things I can, and wisdom to know the difference.”

- Being able to overcome impostor syndrome.

In conclusion

In closing, we may hear that stress kills. Still, perhaps a more appropriate interpretation is that it is our inability to accommodate or allow appropriate recovery from stress, considering our naturally-designed stress response, and how we perceive the impact of stress upon our lives that is becoming the problem.

As fitness experts, perhaps it is time to retrain how we approach the subject of stress in our programming and exercise selection for clients.

References:

- Cannon, W. B., (1926). Physiological regulation of normal states: some tentative postulates concerning biological homeostatics. IN: Pettit, A., & Richet, A.C., Ses amis, ses collègues, ses élèves, Paris, France, Éditions Médicales.

- Sapolsky, R. (2010). Stress and Your Body. Chantilly, VA., The Teaching Company. http://www.thegreatcourses.com/tgc/courses/course_detail.aspx?cid=1585. Retrieved 2013-01-21.

- Crum AJ, and Langer EJ (2007). Mindset matters: Exercise and the placebo effect. Psychological Science, 18(2):165-171.

- Hoehn, K, Marieb. EN. (2010). Human Anatomy and Physiology. San Francisco, CA: Benjamin Cummings

- Sapolsky, RM. (2004). Why Zebras don’t get ulcers. New York, NY: Henry Holt and Company, LLC.

- Keller A, Litzelman K, Wisk LE, Maddox T, Cheng ER, Creswell PD, and Witt WP, (2012). Does the perception that stress affects health matter? The association with health and mortality. Health Psychology, 31(5), 677.

- Selye, H. (1978). The stress of life. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill

The Author

Fabio Comana

Fabio Comana, M.A., M.S., is a faculty instructor at San Diego State University, and University of California, San Diego and the National Academy of Sports Medicine (NASM), and president of Genesis Wellness Group. Previously as an American Council on Exercise (ACE) exercise physiologist, he was the original creator of ACE’s IFT™ model and ACE’s live Personal Trainer educational workshops. Prior experiences include collegiate head coaching, university strength and conditioning coaching; and opening/managing clubs for Club One. An international presenter at multiple health and fitness events, he is also a spokesperson featured in multiple media outlets and an accomplished chapter and book author.